This morning a new strawberry poison dart frog metamorph made its first appearance. Brightened what had been a bit of a gloomy day. Welcome to this thing called life, little one.

A professor of vertebrate zoology

This morning a new strawberry poison dart frog metamorph made its first appearance. Brightened what had been a bit of a gloomy day. Welcome to this thing called life, little one.

Back in June, Dr. Katherine Krynak (Ohio Northern University), John McCall (Michigan Tech. University) and I completed our fifth year of field surveys for Blanchard’s cricket frog, with the help of three awesome student assistants. We have been doing listening surveys for this species at 102 sites in northwestern Ohio since 2017, which builds on a five year data set from the same sites from 2004-2008. This year was a relatively good year for cricket frogs, with at least a third of the sites occupied. Keep your eyes open for a forthcoming analysis of these survey data!

The online early version of our new paper on glass frog communities in old-growth and second-growth rain forests is now available. This paper is the result of seven expeditions over five years to Costa Rica and Trinidad and Tobago with my wonderful student co-authors. Click here to access the online version. Congrats all!

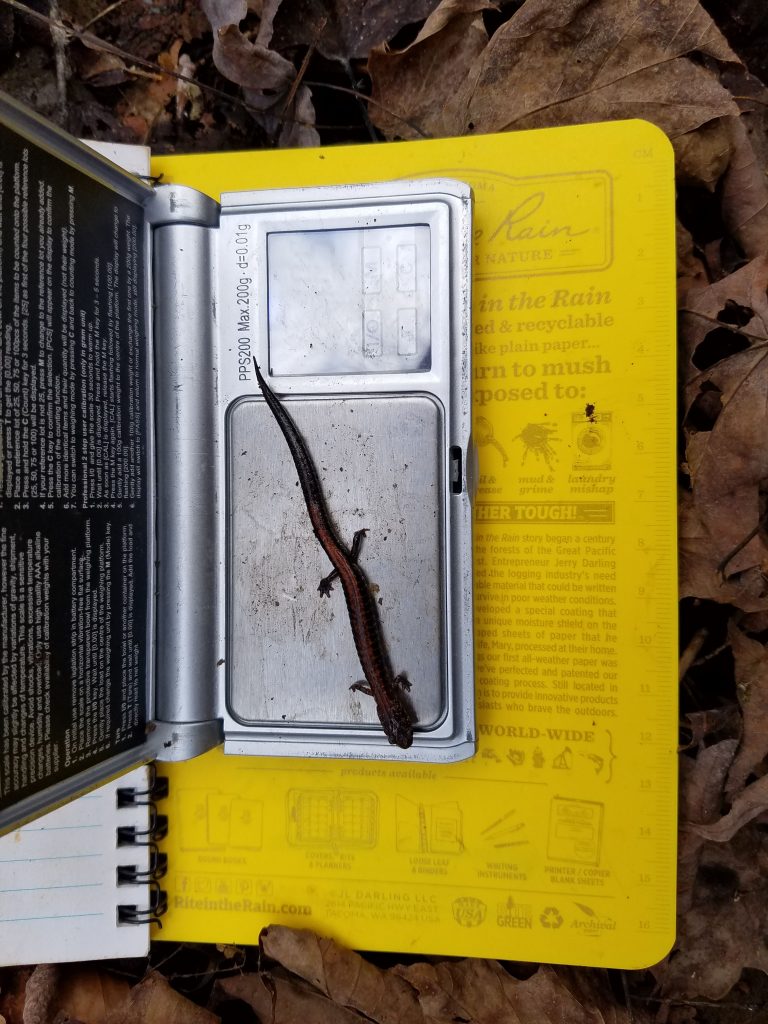

2020 has been a long year for everyone and it was a challenging to finish my salamander fieldwork for this year. I have several large, ongoing projects with local salamanders but under normal circumstances, I would have lots of help from College of Wooster students and the citizen scientists who volunteer with the “Salamander Squad.” Due to restrictions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, however, I didn’t have the help I had gotten used to having. Without all the extra hands, completing my 2020 fieldwork took far longer than usual. But (as of yesterday), it is now complete! Let’s hope for a 2021 that will allow gatherings so we can chase salamanders together once again.

Since 2011, I have been the director of the Fern Valley Field Station, the College of Wooster’s outdoor learning laboratory. This 56-acre property was generously donated to the College by David and Betty Wilkin. Most of the property is forested, however, there is a large field (about 12 acres) that formerly was used for grazing cattle. Currently, this old field is dominated by goldenrod. This past May, we officially started an effort to turn this old field back into a forest by transplanting native tree species into the field.

With protection from white-tailed deer and other herbivores with the plastic tubes, hopefully the trees will grow rapidly and begin to turn this field into a young forest (if they can survive the summer heat). We will be tracking the changes that occur as that process unfolds. Thanks to Oria Daugherty (’21) and Caden Croft (’21) for pitching in. Check out the Fern Valley website to learn more!